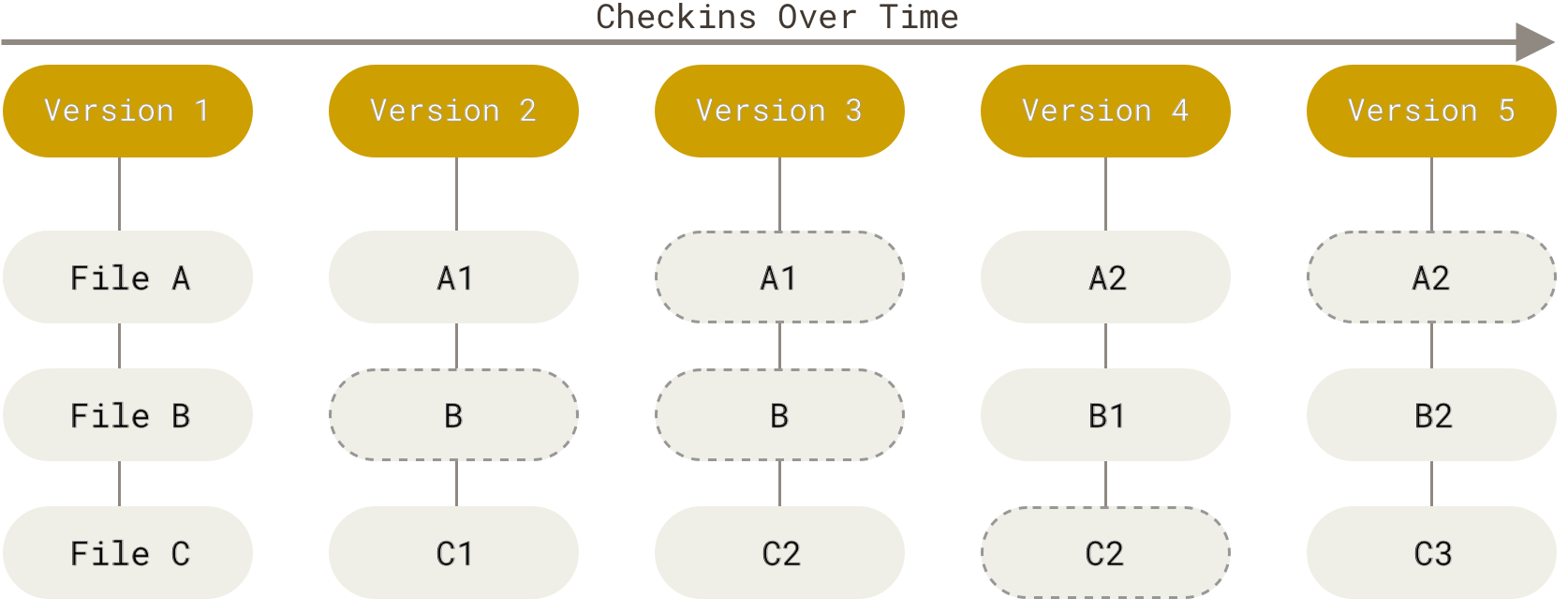

Some [[{9.2} version control is a system that records changes to files|version control systems]] see information as a set of files and changes made to them over time (delta-based version control). Git sees information as a “series of snapshots of miniature file systems”.

It takes a picture of what **all** the files look like when you save them (“[[basic git workflow|commit]]”).

It also doesn’t store / create a *new* file when committing if you haven’t changed anything. Instead, it looks to the previous identical file it already stored.

I see the difference in the picture examples, but still not sure how to put this in my own words. I guess it’s like… Instead of looking at a file being changed individually and pushing that back into a repository, it captures the entire repository when one change is made.

# three states of git files

---

There are three states files can be in with Git:

1. Modified, meaning you’ve made some change.

2. Staged, meaning you’ve marked that change to be included in the next snapshot.

3. Committed, meaning your data has been safely stored.

- “data” meaning an entirely new snapshot?

- Note that Git only *adds* data. It’s hard to actually erase anything. So, even if you’ve deleted some part of a file, it’s still available in Git.

# sections of a git project

---

There are three main sections of a git project:

1. The **Working Tree**, which is a “checkout” of one version of the project where you’ve pulled the database from the git directory to your machine.

2. The **Staging Area**, which is a file with all the information that will go into your next commit. (Technical name is “index”.)

3. The **Git Directory**, which is where git stores the metadata and database for your project. This is what’s copied when you clone a repository to another computer.

# see also

---

- [[pushing my 11ty changes to github]]